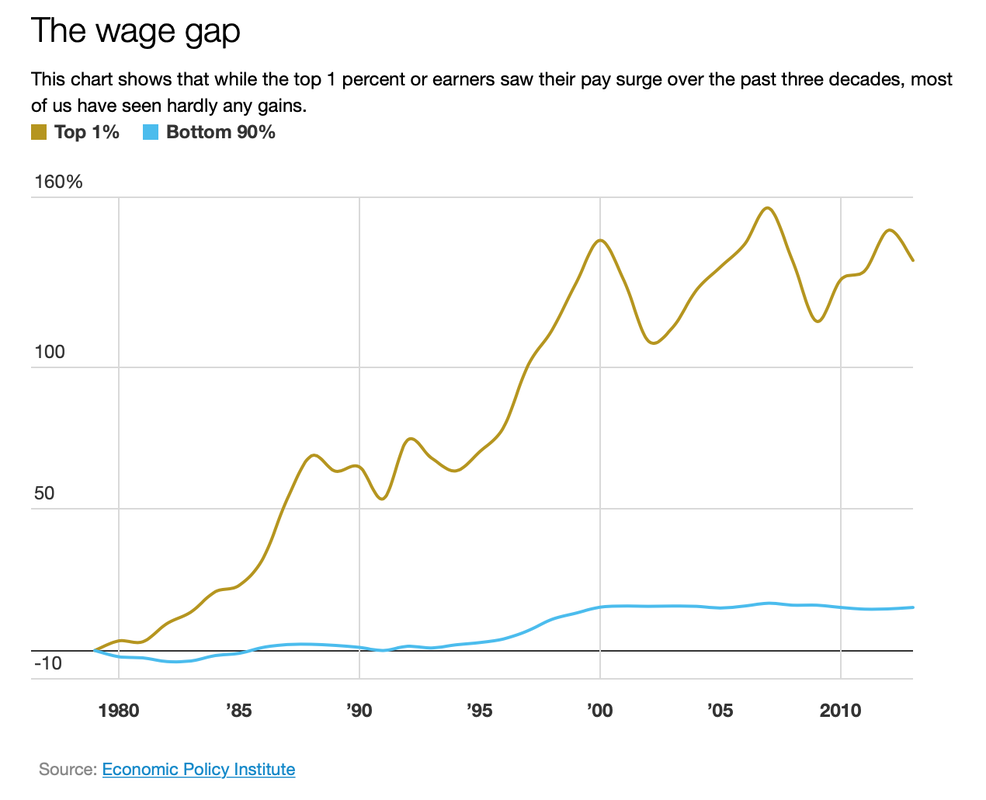

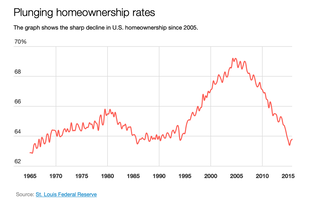

Haunted by the American Dream  The American Dream has always been perceived by Americans as the trend toward upward social mobility for the entrepreneur, the determined, and the hard working. It’s the ability to go from rags to riches—or at least to a prosperous middle class. It is home ownership. It is stable employment--the ability to retire debt-free, and enjoy one’s golden years without fear. Of course, this fantasy has never applied equally to race, class, or gender. Many view the American Dream as the possibility of one’s children doing better, financially, than their parents. However, according to Brookings, “While 90% of the children born in 1940 ended up in higher ranks of the income distribution than their parents, only 40% of those born in 1980 have done so.” For all but the highest paid workers, wages have been in decline for the last 30 years. In 1950 CEOs were paid an average of twenty times the pay of typical workers. That multiple rose to 42-to-1 in 1980, and to 120-to-1 in 2000. The rich grew richer while the poor became poorer. Homeownership rates have recently hit a fifty-year low, below sixty-four percent, in 2015. Many ambitious books have been written about this complex decline in hope for upward social mobility among the poor, so I won’t cover that in depth here. There are, of course, many factors contributing to this trend (some I've already touched on): inflation, wealth inequality, racism, among others.

In 1977 when Jay Anson wrote his pseudo-true haunted house story The Amityville Horror, the American Dream was still achievable for a white middle-class family. This story, written more like true crime than a typical novel, follows the Lutz family as they choose a new home in Amityville, Long Island. With an $80,000 price tag—far below the going rate for this posh neighborhood due to the house having been the site of a mass murder—it is still somewhat above George and Kathy Lutz’s means, but they can’t pass up the opportunity. They decide to overlook the home’s past. After all, they aren’t superstitious people. Like many who attempt to live beyond their means, the Lutz family is just a single disaster away from losing everything. They are a single-income household, attempting to live the 1950s idyllic lifestyle with Kathy at home, filling her days with house-making chores and caring for the children, while George goes off to manage his small company. Throughout the novel, George Lutz frets over how he’s going to pay the bills and he’s shuffling money around from his small business accounts to his private accounts to cover checks he’s already written--even when he knows his business is about to be audited. Everything goes askew when the house turns out to be haunted. The story is full of details of their swift decline in fortune. Doors are ripped off hinges, windows are broken. George watches his wife levitate and listens to his pre-school-aged step-daughter describe conversations with a demon pig as if it were her best friend. Sludgy green goo emanates from a door lock and oozes down walls and staircases. Flies congregate midwinter. A strange hidden room—painted red and reeking of blood—is found in the basement. Kathy Lutz feels the hands of an invisible stranger. Strange smells permeate the air. Even the priest who tried to help them is plagued by stigmata and bedridden by stomach flu three times in three weeks. Ultimately, the Lutzs are driven from the home, leaving all of their possessions behind, and move far away, to California. The real Lutzs, who dreamed up this over-the-top confabulation, were also reportedly in some financial troubles, though that had to have eased significantly after royalties from this book poured in. But I have to wonder, were the Lutzs haunted by ancient demons or by the specter of intractable debt destroying everything they ever thought they wanted? References and Further Reading: Brookings Institute "Is the American Dream Really Dead?" Economic SYNOPSES 2015 I Number 14 "Lagging Long-Term Wage Growth" Economic Policy Institute "CEO Compensation has Grown 940% Since 1978" Wikipedia "Wage Ratio" The Conversation "Is the American Dream Dead?" Investopedia "What Does the American Dream Mean To Different Generations?"

3 Comments

When I think of haunted houses, I frequently think of this Eddie Murphy skit. He’s just so sensible. White people do stick around too long in these stories. As viewers we're all silently shouting at the screens--just get out! But as writers we know that if we have our characters “just get out” there will be no story at all. It’s fine for a comedy skit, but not the blockbuster novel we’re dreaming of writing. Q. Why would a person stay in a haunted house?  As I read Elaine Mercado’s Graves End: A True Ghost Story, I kept thinking about the similarities of her experience in that home to an abusive relationship. Sometimes it’s just not a simple matter to extricate ourselves from the situations we humans find ourselves in. Here are the ways that I felt Elaine Mercado’s experience mirrored an abusive relationship: Whether an abusive relationship takes the form of physical or emotional abuse, the victim of the abuse suffers from low self-esteem. They have been repeatedly made to feel worthless and like there’s no better option.

The abusive cycle. Instances of abusive behavior are often followed by sincere apologies and promises that it will never happen again. Then there is usually a honeymoon period of extreme solicitousness.

Societal pressure. There is less of this these days than in the past, but there can be a lot of pressure--especially from family--to stay together for the kids, or to stick it out through a bad patch, because it will get better.

Gaslighting. Abusers are often adept at making their victims feel as though all of their problems as a couple are the fault of the victim.

Maybe they’ll change. A lot of people in these situations live on the hope that their partner will change.

Dependency. Often people can’t just leave an abusive relationship because they have children with their abuser or they may be inextricably tied financially to them with shared accounts and properties.

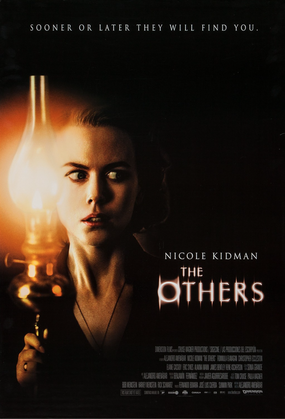

We’ve all read stories with thin premises. As writers it’s important to consider real-world reasons for our character’s motivations so that they make sense to the reader and are believable. While this story is a memoir of a real individual’s experience, I think that we can learn a lot by examining the nature of her reasoning and thought processes and how they may parallel other situations that we may be more familiar with—and bring those ideas with us into the writer’s room.  Warning: there are spoilers in this post! This film, released in 2001, was written, directed, and scored by Alejandro Amenábar and stars Nicole Kidman. The movie was a box office success and critically acclaimed both due to Kidman’s performance and Amenábar’s clever script. I posit that this script is a perfect example of asking all the right “what if” questions in order to arrive at a unique story with a killer surprise ending. When we sit down to write a story we are asking ourselves many “what if” questions as we contemplate every aspect from characterization to plot. I can only presume that Amenábar set out to write a Gothic Horror script that subverted expectations and played with typical notions of time and space. In this essay, I’ll imagine how Amenábar worked through these questions. Perhaps he began with the genre convention of a spooky mansion but asked himself, “what could make this house more spooky?” Perhaps it is half empty and half filled with the previous owner’s belongings, covered with sheets. Maybe it is dark all of the time inside, to make it extra spooky. Then comes the question, “why would it be dark inside all of the time?” Amenabar decides that the story is set just after World War II. The family is so accustomed to living without electricity due to all of the outages during the war that they never bother to have electricity installed. That would make the house much darker inside—especially at night. The inhabitants would be forced to rely on candle and lamp light. That means small pools of flickering light and deep shadows—a perfect setting for one’s mind to play tricks. Perhaps he thought, “This is good, but it would be even better if it were also dark during the daytime. What reason could there be for darkness inside the house during the day?” Perhaps he had heard of the rare disease Xeroderma pigmentosum. One would have to assume that with only 1000 modern cases in the world, there would be people afflicted with the condition in the 1940s, but it would not be well understood. This genetic disease causes an intense and dangerous reaction to sunlight. Most afflicted children do not make it to adulthood because limiting sun exposure is so difficult. This not only fulfills his need to make the enormous mansion dark and spooky even during the day but it also adds an element of high stakes—the children must be protected from light and even the smallest misstep could have dire consequences. Things must be muddled. Let’s make the mother a strict disciplinarian who is clearly off-balance—make the audience wonder if she is on the verge of a nervous breakdown or another form of mental illness. And add three other characters in the form of servants, who sometimes appear to be generous and kind and other times seem to be acting very suspicious. Make the mother desperate for help, such that she takes them on without references. Also, throw in a husband, thought to have died in the war, who is shell-shocked from trench warfare.  Now, Amenábar may have thought, how can I subvert my audience’s expectations? A surprise twist at the end. Yes. Perfect. We always read and watch ghost stories from the human point of view. Is there a way we can turn this on its head? Ah, yes. Write the story from the ghost’s point of view. Can we make that even stranger somehow? The mother is unhinged... perhaps she doesn’t know she’s dead. Perfect. What other elements could be added to make things extra creepy? The little girl could see things that the adults can’t. Throw in a photo album full of death portraits, mysterious fog, unseen children crying and playing, doors that shut on their own, and pianos that play themselves. Anything else? Make the mother so neurotic she not only closes every door, she locks them. Perhaps one more genre convention to round things out. A seance led by a spiritualist. Yes, that plays into the twist at the end perfectly. I hope Alejandro Amenábar will forgive me for supposing I can imagine his thought processes, but I found this plot and characterization so fascinating, so refreshingly new, that I had to think about how he may have come up with it. Thinking this way—in particular: how do I subvert the reader/watcher’s expectations and surprise them—can really make for a fresh take on a common story. Readers want to read stories that feel comfortable and familiar while also surprising them. It behooves us as writers to imagine what elements of common genre conventions we wish to use on their face and which ones we want to contort into something new. In this case, the dark, lonely mansion and the mentally ill woman living in the house are genre conventions. But most of the rest of this story feels entirely new. I think that is the secret to this movie’s success. Kidman’s incredible performance didn’t hurt either. Postscript: Unfortunately, at the time of this writing, The Others is not available on any US streaming service. I believe this may have something to do with a television adaptation in development.

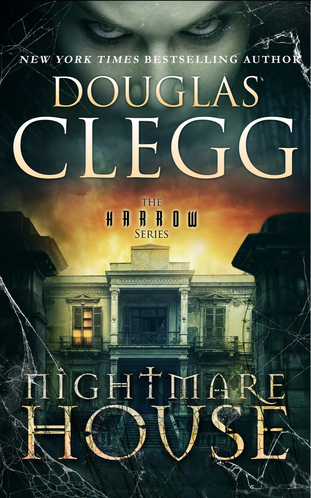

Delete both the cover and the publishing date from Douglas Clegg’s Nightmare House and some readers may have a difficult time guessing when it was actually published (my kindle edition was published in 2012). Set in the early twentieth century, this delicious gothic horror novel of Esteban “Ethan” Gravesend’s deeply personal encounter with his inherited haunted mansion utilizes many of the elements of novels from the past. As I read, I was reminded of the flavor of such classics as Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, by Charlotte Bronte and Emily Bronte (both published in the mid-nineteenth century), but I noted that several reviewers on the book’s Amazon page mentioned Henry James’s Turn of the Screw (known to be greatly inspired by Jane Eyre—but with ghosts) which was published just at the turn of the twentieth century and is also a gothic horror novel.

The prologue sets the stage by describing the narrator/protagonist’s entire life, from birth, including his relationships with his parents (and a brief summary of their lives), as well as his remembrances of the titular mansion from childhood when his grandfather was still alive. This convention of the past is no longer considered normal or acceptable in popular fiction. As modern writers we are expected to begin our novels in medias res (into the midst of things, without preamble). Chapter one continues on in this vein, discussing more of Ethan’s life, his marriage, and more remembrances of his grandfather and the estate Harrow he will one day inherit from him. In this novel, I found some of this tedious, but only briefly, because the details were not only interesting—they became pertinent later in the story. By part six of chapter one, the story actually begins. Another interesting device Clegg used from popular fiction’s more distant past is the use of a digression. Digressions are interruptions in the flow of the novel to temporarily switch to another topic. In this novel, these occurred whenever the elderly Ethan interrupts the narrative of the story to tell the reader something he deems important. Traditionally these were often used rhetorically, to further convince a reader of the veracity of a claim. I believe Clegg used these digressions consciously as a stylistic choice to create the feeling of a period gothic novel. Dark, disturbing family secrets also figure large in all of the novels mentioned, usually revealed toward the endings of these novels, often as part of the climax. Here, too, this story reveals some disquieting secrets. Clegg also utilizes what I assert is another convention of these novels from the past—the orphaned child, the unloved child, or the unhappy childhood. Just like Jane Eyre and Heathcliff (of Wuthering Heights) Ethan’s childhood is not what it should have been. His mother pretends to be an invalid and secretly sleeps with her “doctor.” And his father seems to abhor him. The reasons for these attitudes is revealed in the exciting climax of the story. Clegg’s use of language also harkens back to an earlier time. It’s just that little bit more flowery, with more complex sentence structure, than we tend to use today. The text was still quite clear and easy to read, however. He didn’t take this affectation too far. I found his approach effective. Here’s an example: My young life was uneventful save for my naming. My mother—since the accident that precipitated my birth—claimed a weak heart. Her many medications were famous among us: she could not leave her bed without a spoon of some remedy; she could not kiss my father good morning without some wee dram of medical potion to get her heart to its normal capacity; and she often spent months at spas in Saratoga and across the sea—leaving me with a nanny and my father, neither of whom I particularly liked.

Douglas Clegg intentionally used writing conventions of the past to give his novel the distinct flavor of a period gothic novel. He utilized slightly more antiquated language, digressions in his narrator’s voice, an unhappy childhood for his protagonist, disturbing family secrets, and a very detailed summary of the protagonist’s life up until the moment the story begins. I found Clegg’s use of these elements in Nightmare House to be not only effective but also charming. As a young adult I was quite enamored with the Brontes’s works and adaptations of their works as well as other period dramas so perhaps it’s no surprise that I found this novel appealing as well.

A footnote: I could easily have explored further how Clegg utilized gothic novel conventions and/or elements of American Romanticism in this piece, but I felt that the elements I mentioned would be more useful to modern writers of popular fiction. (This could quite easily turn into a full-blown academic treatise.) If you wish to explore these elements further, these sites present quick and easily digestible summaries: Invaluable on Gothic Literature ThoughtCo on American Romanticism *Some links in this post are affiliate links which reward me with a tiny commission at no cost to you. |

Jennifer Foehner WellsI'm an author of the space-opera variety. Archives

April 2022

Categories |