|

In the early 1980s Dan Aykroyd read an article about quantum physics and parapsychology in the American Society of Psychical Research Journal and then watched 1950s classic ghost comedies like the 1951 movie Ghost Chasers. This gave him the idea to reinvent the ghost comedy including the context of contemporary scientific research in physics and parapsychology. This ultimately would become the 1984 beloved classic horror-comedy film Ghostbusters. And with that, Aykroyd efficiently neutered the horror of the paranormal by using science to make it manageable and transmuting it to comedy.

This movie is an unsocialized adolescent male nerd’s fever dream. Our protagonists are all nerds with multiple PhDs and employed by Columbia University in New York City. When their fortune turns to failure and they’re fired by Columbia just when they’re on the verge of a breakthrough, they start up a Ghostbusting venture. Egon Spengler, played by Harold Ramis, with multiple advanced degrees including parapsychology and nuclear engineering, is easily the biggest brain of the operation. He’s a pure science cultist, stating at one point that his hobby is collecting “spores, molds, and fungus.” Ray Stantz, portrayed by Dan Aykroid, is an expert in paranormal history and metallurgy and has a child-like enthusiasm about his work. These two characters invent the scientific tools used to capture and store nuisance ghosts. Peter Venkman, played by Bill Murray, has PhDs in both parapsychology and psychology. A would-be charming lecher, he depends on Egon and Ray to explain the necessary science and seems to be more interested in using rigged studies of paranormal phenomena like ESP to seduce attractive female students. Egon and Ray developed the tech behind the PKE Meter (PKE = psychokinetic energy), the Proton Pack (the backpack equipment that generates the “streams” of protons and nuclear energy they use to capture ghosts), the Trap and the storage facilities. Egon was the one who warned against crossing the streams. “Try to imagine all life as you know it stopping instantaneously and every molecule in your body exploding at the speed of light.” Ray followed with, “Total protonic reversal.” They fail. They try again. They develop better technology and begin to succeed at trapping and storing various types of ghosts. They grow in fame and fortune. And then are met with comical bureaucratic resistance. At the climax of the movie, Egon saves the day (and Earth from domination by an evil demon from another dimension) by evoking theoretical physics. “I have a radical idea. The door swings both ways. We could reverse the particle flow through the gate. We’ll cross the streams.” Then there’s the comedic discussion of how likely they are to live through the attempt—which Egon admits is only a slight chance, but it’s their only hope to defeat Gozer (transformed into the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man.). Part of the comedy of the 1984 film is the cheesy hand-wavey nature of the science that’s employed. But in the 2016 all-female Ghostbusters remake, director Paul Feig wanted the science to feel more legitimate, so he employed physicists from MIT and the DOE, Drs. James Maxwell and Lindley Winslow, to bring not only their expertise, but also their leftover lab junk to the screenplay and the set, respectively. Winslow theorized that the ghosts in Ghostbusters are made up of neutrinos because “they go through anything.” Maxwell, a particle physicist, is responsible for re-inventing the proton pack. Instead of using the cyclotron described in the 1984 film, Maxwell theorized the 2016 Ghostbusters would use a synchotron, a circular particle accelerator, like the Large Hadron Collider. Operating incredibly high magnetic fields on this scale would require cryogenic temperatures so the updated proton pack would require something like liquid helium as a coolant. The main obstacle in bringing such a device to reality would be fitting the tech into a backpack compact and light enough to actually wear. Winslow made sure that the equations on Erin Gilbert’s (Kristen Wiig) whiteboard were real and accurate. Textbooks and other props in Gilbert’s office were rented from another female physicist’s office because Feig (the director) liked how her office looked. Like the original Ghostbusters, the reboot features three scientists. Abby Yates (Melissa McCarthy) and Erin Gilbert (Kristen Wiig) are particle physicists interested in the paranormal. Jillian Holtzmann (Kate McKinnon) is an engineering physicist. As the movie begins, Erin is working toward tenure at Columbia, which is ultimately refused, effectively resulting in her being fired (an homage to the 1984 film). Abbey and Jillian are working in the basement of the Higgins Institute of Science in NYC. While the storyline is quite different from the first movie, the reboot still uses science to explain and defeat paranormal phenomena. Just like in the first movie, there are harrowing moments, but as their knowledge grows and their experimental devices become more effective, they are capable of defeating not only ghosts, but erstwhile gods. While the original 1984 movie was a box office hit and one of the most successful comedies of that year, the 2016 reboot didn’t fare as well. They are both highly entertaining movies in my opinion--they simply employ comedy of different flavors. While the 1984 movie made a lot of childish jokes at women’s expense and employed a lot of goofy slapstick comedy and hyperbolic humor, the 2016 reboot acknowledged that, replied to it, and had its own flavor of quirky characterization that feels fresh and timely by comparison, especially to a more progressive or educated audience. Regardless of those elements, the concept was the same—use science to bring the inscrutable to light, defeat the paranormal bad guy, and make it funny.

2 Comments

The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty is truly a classic of the genre. Published in 1971, Blatty was inspired to write the book after hearing about a case of possession and exorcism that occurred in 1949 involving a teenaged boy in Maryland. Our instructor paired this book with the 2005 movie The Exorcism of Emily Rose, a modern tale of a college-aged American woman, which is based on the true story of Anneliese Michel in early 1970s Germany. (There have also been two other films made about Michel’s ordeal.)

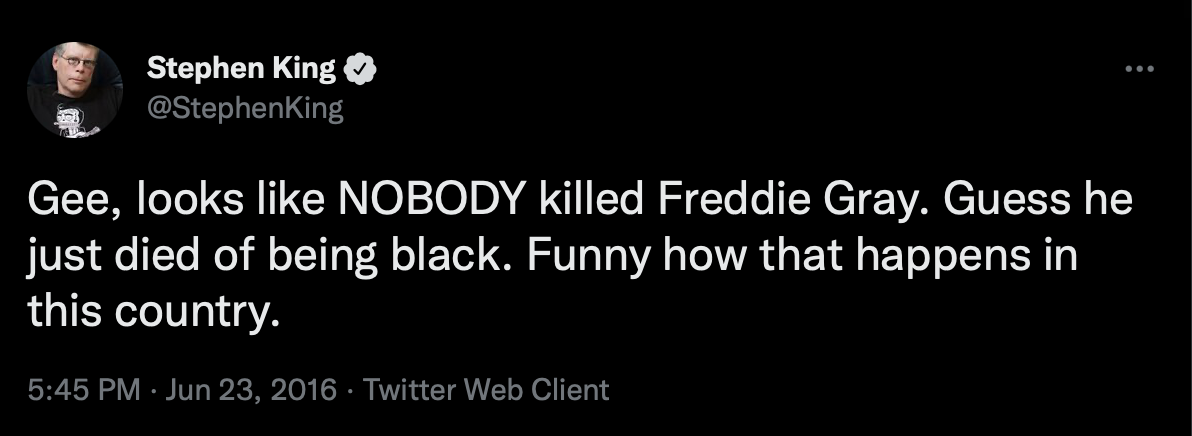

Interesting parallels and differences can be drawn between these two narratives. Both involve young women, though Blatty’s possessed character, Regan MacNeil, was much younger, about eleven years old. In Rose, the possessed woman has just begun college, so we can assume she was eighteen or nineteen. Both seem to be unlikely candidates for faking possession—Regan simply based on age and Emily because she is a devout Christian. In Exorcist, psychological illness was ruled out. In Rose, Emily's mental condition was a mystery throughout. These two stories take different approaches. Exorcist is told in a linear fashion from the points of view primarily of her mother and the Catholic priest, Father Damien Karras, who becomes intimately involved with the case. Rose is more of a courtroom drama which goes back and forth in time to depict events from the point of view of whomever is speaking. For example, if a witness for the prosecution is relating their version of what happened, Emily is shown having epileptic fits and psychotic breaks, but when the Catholic priest Father Richard Moore delivers his explanations, Emily is portrayed as being truly demonically possessed. This introduces another element of uncertainty in the courtroom as well as in the viewer of the film. For me, the most fascinating parallel between the two stories lies in the willingness of both priests to sacrifice their lives—in the case of Father Karras, potentially even his afterlife—in their service. In The Exorcist, we are denied the opportunity to see Karras’s internal reaction to having the demon leave the child and enter his own body subsequent to him taunting the demon. This, I believe, is a flaw in this otherwise compelling narrative. Once the demon enters his body, we know that Karras leaps from the window to kill himself and block the demon from invading another human body. What the book fails to explain is that the Catholic religion teaches that suicide is a sin, and that Karras would be dooming himself to eternal damnation in that moment--quite a sacrifice to make. Throughout the novel Karras was tortured by his loss of faith, and therefore found it difficult to believe that Regan was actually possessed—so in the moment the demon possessed him he, at the very least, had to finally be certain of the existence of demons, which makes his sacrifice all the more poignant. The priest in Rose is equally willing to sacrifice, at least his life on this Earthly plane. Father Moore shows no signs of questioning his faith, or of doubting Rose’s possession. But the man is willing to risk spending the rest of his life in prison so that he may publicly tell Emily Rose’s story in order that her sacrifice would not be in vain. This is why he refuses plea bargains and insists on testifying in the courtroom, including reading aloud a letter Emily left for him. In this letter, Emily explains that she had a vision of speaking with the Virgin Marry who told her that she could be freed from her torment and ascend to heaven, or she could continue on, suffer greatly, but also serve as a reminder to humanity of the existence of the supernatural realm. Emily chose to see her ordeal through to the end. In both stories someone that is possessed dies, making a sacrifice for the greater good. In The Exorcist we assume that Father Karras’s death will protect others at the risk of damning his own soul. In Rose, Emily’s sacrifice is made to convince others of the existence of God in order to save their souls. In Exorcist, Blatty develops quite a few characters: the mother, Father Karras, even the male housekeeper. However, Blatty gives us very little characterization of Regan, the possessed. In a similar fashion most of the characterization in Rose is very shallow. The defense attorney probably gets the most screen time and yet even she is little more than a stock character. Both stories seek to shock us. Blatty has his little girl uttering obscenities and becoming freakishly strong and violent. Rose is more interested in chilling our blood with jump scares, animalistic screaming, horrific contortions of the young woman’s body, and animal attacks. Rose has a little bit more of the elements of more cheesy slasher horror. Both modes of storytelling are effective at what they set out to do. For me, though, I found the novel to be more compelling. I was particularly drawn to Father Karras's internal struggle. There is a reason that this novel's a classic that even young people today have heard of. Note: I haven’t seen the iconic movie version of The Exorcist (the screenplay was also written by Blatty) but the book is superbly written and the audio book (published in 2011)—whoa, Nellie!—the reading of the text is performed by the author and the man was (Blatty passed in 2017 at age 89) extremely gifted. If I hadn’t caught the first few seconds of the intro to the book, I would have assumed that the narrator was a consummate voice actor. It is a stunning performance including distinct vocal modalities for each character and a huge range of emotions.  I have seen first-hand that Black folks are exhausted by explaining race issues to white people. And yet they are required to do so again and again, usually because they are the only “expert” on the topic in the room simply by being there. Our culture is changing, waking up, and though it would be profane for me as a white woman to explain to a Black individual what their own experience means, I can, at the very least, educate other white folks on our collective blind spots concerning race—to the best of my ability. I hate seeing well-meaning but poorly informed white writers making the same old tired mistakes over and over again. So my goal here is to educate. I write inclusively in my fiction for that reason—but also so that Black individuals can see themselves in fiction as more than just a token representative. As you will soon see, there is more than one way in which King utilized race badly in The Shining and white writers can learn a lot from his mistakes. When the character of Dick Halloran popped up in the novel, I was surprised. I hadn’t read any King, but I’ve certainly heard people discuss his work for years. And I had gotten the impression that King wasn’t the sort of white male writer to include Black characters except in the capacity of either: a.) the Token Black Person or b.) the Black Person is the First to Die (or exists to die). I had forgotten that (at least) one more category exists: c.) The Magical Black Person. I’m referring to the novel, of course—in Kubrick’s movie adaptation poor Dick Halloran is ALSO forced into the role of both a and b. What is the Magical Black Person trope? Here’s how Wikipedia defines it (click on the link to read the entire entry if you want to learn more): The Magical Negro is a supporting stock character in fiction who, by use of special insight or powers, often of a supernatural or quasi-mystical nature, helps the white protagonist get out of trouble. African-American filmmaker Spike Lee popularized the term, deriding the archetype of the "super-duper magical negro" in 2001 while discussing films with students at Washington State University and at Yale University. Wikipedia goes on to list occurrences of this trope in film, television, and literature. The Shining shows up on both the film and literature list. But it doesn’t stop there. Writer and poet Scott Woods gives a lecture entitled “Stephen King’s Magical Negroes.” Woods takes this lecture seriously and keeps up with everything King writes (and has ever written) as well as every adaptation to television and film so he can update his lecture accordingly. His Medium essay on the topic is an interesting read. He notes, If you only ever watched The Green Mile, you’d have a decent-enough grasp on the problem here, considering John Coffey is not only King’s most famous Magical Negro, but perhaps the greatest Magical Negro of all time, right down to the religious hat-tip of his initials. You see, Dick Halloran isn’t King’s only magical Black man. He was just the first. King may have thought he’d written himself into a corner in The Shining. It is commonly accepted that in literature a protagonist must have the means and ability to save themself—and then do so. That’s usually the point of the story. But by making the protagonist a five-year-old boy—even a magical one--King may have worried that it would be impossible to believe that this particular protagonist could get himself out of serious trouble on his own. The kid needed an assistant strong enough to pick up his battered mother and carry her out of the Overlook Hotel before it blew. I posit that while reading it’s easy to forget that Danny Torrance is only five. His intelligence, actions, speech patterns—all are those of a much older person. I am the mother of two incredibly intelligent young men. They are the sons of an author who favors a large vocabulary. And they, at age 10, couldn’t rival Danny Torrance at age five. It’s as if the shine has increased his experience of the world 100-fold. In fact when Danny pleads with the hotel near the climax of the story, (I’m just five!) he cried to some half-felt presence in the room. (Doesn’t it make any difference that I’m just five?) I sort of twitched. That reminder shocked me. Danny Torrance is so young he has never met another person like himself until he meets Halloran. Halloran takes the time to explain the shine to Danny and the words that he speaks rebound through Danny’s mind throughout the rest of the novel. Of course Halloran was wrong about one thing—he doesn’t take into account that the sheer supernatural power Danny wields could fuel the hotel. Or that it might want all that power for itself. So in the end Danny is forced to psychically scream in order to get Halloran to come back to this remote spot in Colorado all the way from Florida. Which he does. And though he immediately gets beat up by the Jack/Hotel construct, he does manage to get Wendy and Danny out of the hotel—and away to safety via a snowmobile in the deadly sub-zero winter temperatures. One might say—hey, Jen, this was 1977. Give King some props. He made a Black man a pivotal character in this novel. He didn’t have to do that. Keep reading. As we watch Halloran struggle to get to Danny, Halloran is subjected to what felt like (to me) constant racial slurs, including the N-word. This was another of King’s painful mistakes. I’m sure he thought he was writing realism. In his essay, Scott Woods calls this the “Tarantino Defense.” But for African American readers, the result is the same. Whether a writer is racist and writing his own beliefs or simply writing characters who would realistically say those horrible things, the psychological damage of reading them is the same. As a white woman, I felt sick reading them. Why are they needed in this novel, in any novel? What purpose does it serve? King could have toned it down to Halloran having feelings of being unwanted or hearing unkind words and every living American would know what he meant without resorting to such backwards and sickening language. Did he think no African American would ever pick up this novel? Did he think that if they did they were inured to such violent language? No one becomes immune to hearing or reading damaging words like that. Words have power. If we don't know that, we shouldn't be writing. While The Shining is brilliant in so many ways—while it was a trailblazer in the Horror genre, a classic—things that shine are subject to tarnish. The use of the magical Black person and the liberal use of realistically stark and biting racial epithets mars this novel. I realize I may be pissing off serious King fans. But remember—no single thing is perfect. Let us go forth and always try to do better. Post Script King may have long been a vocal liberal, but according to Woods, it’s only in the last few years that King has become woke enough to tweet something like this from 2016, right after the acquittal of the police who killed Freddie Gray: Woods also noted significant changes among the pages of King’s 2017 novel Sleeping Beauties which King dedicated to Sandra Bland, the Texas woman who was wrongfully arrested for driving while Black and then mysteriously died in her jail cell three days later.

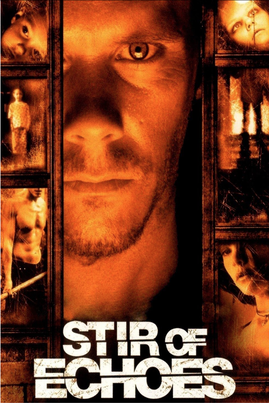

Stephen King is 74 years old. If he can change at that age, we all can.  Stir of Echoes demonstrates a post 9/11 trend I’ve noticed in dystopian literature—that of allowing the protagonist to have agency and to effect change in their world or surroundings. For example, in The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood, Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell the protagonists have no agency and the central story problem is not resolved. But after September 11, 2001 popular dystopian novels like The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, Ready Player One by Ernest Cline, and Divergent by Veronica Roth allow the protagonists to reshape their world for the better. Now I realize we have been studying horror and not dystopian literature, but since they both fall into the realm of speculative fiction, I think this is an interesting quality to note, though in the case of these horror/ghost stories I don’t see it as a trend with a specific pivotal date. In many of the stories we’ve read and watched this semester the end of the book reflects the conclusion of the story, but not necessarily a resolution of the original problem i.e. the haunting. In The Haunting of Hill House, Paranormal Activity, Nightmare House, The Others, and The Amityville Horror, the haunting continues throughout the story and beyond. By contrast, Stir of Echoes, Hell House, Ghost Story, and Grave’s End each give the protagonists the means to end the haunting. Allowing the protagonists to find a solution doesn’t just kill the chance for either a sequel or a franchise to be developed around the same premise, it also removes the horror element. Horror could be defined as contact with the sublime—a manifestation of the unknowable, the awe-inspiring, the terrifying, something we mere mortals cannot measure or understand. But if the protagonist comes to at least a minimal understanding of the central problem of the story—enough to eliminate the problem or to set things right again—then they have peeked into the sublime and learned something. And that removes the horror. When Kevin Bacon, as Tom Wiztsky, finds himself confronted with bizarre and frightening messages from beyond the grave, he doesn’t run away—instead he seeks to understand. He sees the messages as clues, as some riddle he can solve, despite the fact that the process seems to be driving him mad. And even when his wife loses faith in him, he declares that following this trail of clues is the most significant, most important thing he’s ever done in his life. We find out how deep his passions run when he digs up the entire back yard, then proceeds to rent tools to break through the concrete flooring in the tiny basement space under his kitchen. Ultimately, very much like one would in a mystery story, Wiztsky solves the problem that caused the spirit of a young woman to haunt his house. He brings her killers to justice which frees her soul from its dark despair and allows her to move on. The haunting has ended. Similarly, the protagonists of Hell House, Ghost Story, and Grave’s End solve their respective mysteries and the haunting element is eliminated. That’s not to say Stir of Echoes didn’t have frightening or horrific moments—there were a few moments of body horror here and there that are still making me cringe. And of course the way that Tom Wiztsky seemed to be losing control of his life was also frightening. I don’t necessarily see this as a similar trend to that which I have noted in dystopian fiction, but more of a stylistic choice. I think most readers find an ending with a full resolution to be more satisfying, and uplifting--and less frightening than one in which there is no hope of solving the story problem. But if an author’s goal is to curdle the blood and make the novel hard to shake for a reader, I would suggest not allowing the central story problem to resolve. |

Jennifer Foehner WellsI'm an author of the space-opera variety. Archives

April 2022

Categories |