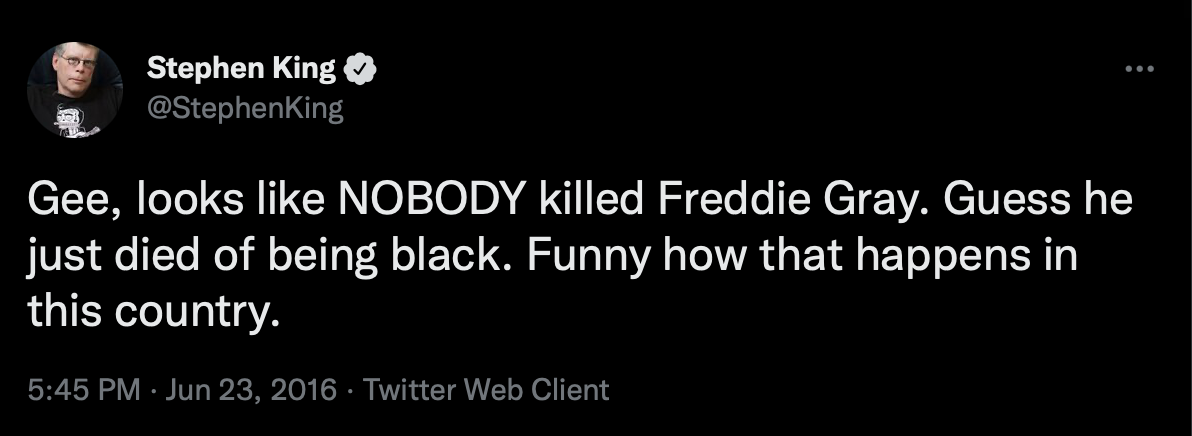

I have seen first-hand that Black folks are exhausted by explaining race issues to white people. And yet they are required to do so again and again, usually because they are the only “expert” on the topic in the room simply by being there. Our culture is changing, waking up, and though it would be profane for me as a white woman to explain to a Black individual what their own experience means, I can, at the very least, educate other white folks on our collective blind spots concerning race—to the best of my ability. I hate seeing well-meaning but poorly informed white writers making the same old tired mistakes over and over again. So my goal here is to educate. I write inclusively in my fiction for that reason—but also so that Black individuals can see themselves in fiction as more than just a token representative. As you will soon see, there is more than one way in which King utilized race badly in The Shining and white writers can learn a lot from his mistakes. When the character of Dick Halloran popped up in the novel, I was surprised. I hadn’t read any King, but I’ve certainly heard people discuss his work for years. And I had gotten the impression that King wasn’t the sort of white male writer to include Black characters except in the capacity of either: a.) the Token Black Person or b.) the Black Person is the First to Die (or exists to die). I had forgotten that (at least) one more category exists: c.) The Magical Black Person. I’m referring to the novel, of course—in Kubrick’s movie adaptation poor Dick Halloran is ALSO forced into the role of both a and b. What is the Magical Black Person trope? Here’s how Wikipedia defines it (click on the link to read the entire entry if you want to learn more): The Magical Negro is a supporting stock character in fiction who, by use of special insight or powers, often of a supernatural or quasi-mystical nature, helps the white protagonist get out of trouble. African-American filmmaker Spike Lee popularized the term, deriding the archetype of the "super-duper magical negro" in 2001 while discussing films with students at Washington State University and at Yale University. Wikipedia goes on to list occurrences of this trope in film, television, and literature. The Shining shows up on both the film and literature list. But it doesn’t stop there. Writer and poet Scott Woods gives a lecture entitled “Stephen King’s Magical Negroes.” Woods takes this lecture seriously and keeps up with everything King writes (and has ever written) as well as every adaptation to television and film so he can update his lecture accordingly. His Medium essay on the topic is an interesting read. He notes, If you only ever watched The Green Mile, you’d have a decent-enough grasp on the problem here, considering John Coffey is not only King’s most famous Magical Negro, but perhaps the greatest Magical Negro of all time, right down to the religious hat-tip of his initials. You see, Dick Halloran isn’t King’s only magical Black man. He was just the first. King may have thought he’d written himself into a corner in The Shining. It is commonly accepted that in literature a protagonist must have the means and ability to save themself—and then do so. That’s usually the point of the story. But by making the protagonist a five-year-old boy—even a magical one--King may have worried that it would be impossible to believe that this particular protagonist could get himself out of serious trouble on his own. The kid needed an assistant strong enough to pick up his battered mother and carry her out of the Overlook Hotel before it blew. I posit that while reading it’s easy to forget that Danny Torrance is only five. His intelligence, actions, speech patterns—all are those of a much older person. I am the mother of two incredibly intelligent young men. They are the sons of an author who favors a large vocabulary. And they, at age 10, couldn’t rival Danny Torrance at age five. It’s as if the shine has increased his experience of the world 100-fold. In fact when Danny pleads with the hotel near the climax of the story, (I’m just five!) he cried to some half-felt presence in the room. (Doesn’t it make any difference that I’m just five?) I sort of twitched. That reminder shocked me. Danny Torrance is so young he has never met another person like himself until he meets Halloran. Halloran takes the time to explain the shine to Danny and the words that he speaks rebound through Danny’s mind throughout the rest of the novel. Of course Halloran was wrong about one thing—he doesn’t take into account that the sheer supernatural power Danny wields could fuel the hotel. Or that it might want all that power for itself. So in the end Danny is forced to psychically scream in order to get Halloran to come back to this remote spot in Colorado all the way from Florida. Which he does. And though he immediately gets beat up by the Jack/Hotel construct, he does manage to get Wendy and Danny out of the hotel—and away to safety via a snowmobile in the deadly sub-zero winter temperatures. One might say—hey, Jen, this was 1977. Give King some props. He made a Black man a pivotal character in this novel. He didn’t have to do that. Keep reading. As we watch Halloran struggle to get to Danny, Halloran is subjected to what felt like (to me) constant racial slurs, including the N-word. This was another of King’s painful mistakes. I’m sure he thought he was writing realism. In his essay, Scott Woods calls this the “Tarantino Defense.” But for African American readers, the result is the same. Whether a writer is racist and writing his own beliefs or simply writing characters who would realistically say those horrible things, the psychological damage of reading them is the same. As a white woman, I felt sick reading them. Why are they needed in this novel, in any novel? What purpose does it serve? King could have toned it down to Halloran having feelings of being unwanted or hearing unkind words and every living American would know what he meant without resorting to such backwards and sickening language. Did he think no African American would ever pick up this novel? Did he think that if they did they were inured to such violent language? No one becomes immune to hearing or reading damaging words like that. Words have power. If we don't know that, we shouldn't be writing. While The Shining is brilliant in so many ways—while it was a trailblazer in the Horror genre, a classic—things that shine are subject to tarnish. The use of the magical Black person and the liberal use of realistically stark and biting racial epithets mars this novel. I realize I may be pissing off serious King fans. But remember—no single thing is perfect. Let us go forth and always try to do better. Post Script King may have long been a vocal liberal, but according to Woods, it’s only in the last few years that King has become woke enough to tweet something like this from 2016, right after the acquittal of the police who killed Freddie Gray: Woods also noted significant changes among the pages of King’s 2017 novel Sleeping Beauties which King dedicated to Sandra Bland, the Texas woman who was wrongfully arrested for driving while Black and then mysteriously died in her jail cell three days later.

Stephen King is 74 years old. If he can change at that age, we all can.

4 Comments

Hey--you aren't necessarily going to know this stuff unless you've studied African American literature, watch a lot of Key and Peele :), or live with a professor of African American literature (like I do). I'm learning new stuff every single day about the lived experience of my Black partner and our greater culture. I'm so happy to have helped you. Thank you for letting me know, Katie.

Reply

Michelle Skeen

4/9/2022 12:32:31 pm

Jen-

Reply

4/10/2022 01:27:39 pm

You're welcome. And yes--they have changed. Let us hope they continue to do so.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Jennifer Foehner WellsI'm an author of the space-opera variety. Archives

April 2022

Categories |