|

In the early 1980s Dan Aykroyd read an article about quantum physics and parapsychology in the American Society of Psychical Research Journal and then watched 1950s classic ghost comedies like the 1951 movie Ghost Chasers. This gave him the idea to reinvent the ghost comedy including the context of contemporary scientific research in physics and parapsychology. This ultimately would become the 1984 beloved classic horror-comedy film Ghostbusters. And with that, Aykroyd efficiently neutered the horror of the paranormal by using science to make it manageable and transmuting it to comedy.

This movie is an unsocialized adolescent male nerd’s fever dream. Our protagonists are all nerds with multiple PhDs and employed by Columbia University in New York City. When their fortune turns to failure and they’re fired by Columbia just when they’re on the verge of a breakthrough, they start up a Ghostbusting venture. Egon Spengler, played by Harold Ramis, with multiple advanced degrees including parapsychology and nuclear engineering, is easily the biggest brain of the operation. He’s a pure science cultist, stating at one point that his hobby is collecting “spores, molds, and fungus.” Ray Stantz, portrayed by Dan Aykroid, is an expert in paranormal history and metallurgy and has a child-like enthusiasm about his work. These two characters invent the scientific tools used to capture and store nuisance ghosts. Peter Venkman, played by Bill Murray, has PhDs in both parapsychology and psychology. A would-be charming lecher, he depends on Egon and Ray to explain the necessary science and seems to be more interested in using rigged studies of paranormal phenomena like ESP to seduce attractive female students. Egon and Ray developed the tech behind the PKE Meter (PKE = psychokinetic energy), the Proton Pack (the backpack equipment that generates the “streams” of protons and nuclear energy they use to capture ghosts), the Trap and the storage facilities. Egon was the one who warned against crossing the streams. “Try to imagine all life as you know it stopping instantaneously and every molecule in your body exploding at the speed of light.” Ray followed with, “Total protonic reversal.” They fail. They try again. They develop better technology and begin to succeed at trapping and storing various types of ghosts. They grow in fame and fortune. And then are met with comical bureaucratic resistance. At the climax of the movie, Egon saves the day (and Earth from domination by an evil demon from another dimension) by evoking theoretical physics. “I have a radical idea. The door swings both ways. We could reverse the particle flow through the gate. We’ll cross the streams.” Then there’s the comedic discussion of how likely they are to live through the attempt—which Egon admits is only a slight chance, but it’s their only hope to defeat Gozer (transformed into the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man.). Part of the comedy of the 1984 film is the cheesy hand-wavey nature of the science that’s employed. But in the 2016 all-female Ghostbusters remake, director Paul Feig wanted the science to feel more legitimate, so he employed physicists from MIT and the DOE, Drs. James Maxwell and Lindley Winslow, to bring not only their expertise, but also their leftover lab junk to the screenplay and the set, respectively. Winslow theorized that the ghosts in Ghostbusters are made up of neutrinos because “they go through anything.” Maxwell, a particle physicist, is responsible for re-inventing the proton pack. Instead of using the cyclotron described in the 1984 film, Maxwell theorized the 2016 Ghostbusters would use a synchotron, a circular particle accelerator, like the Large Hadron Collider. Operating incredibly high magnetic fields on this scale would require cryogenic temperatures so the updated proton pack would require something like liquid helium as a coolant. The main obstacle in bringing such a device to reality would be fitting the tech into a backpack compact and light enough to actually wear. Winslow made sure that the equations on Erin Gilbert’s (Kristen Wiig) whiteboard were real and accurate. Textbooks and other props in Gilbert’s office were rented from another female physicist’s office because Feig (the director) liked how her office looked. Like the original Ghostbusters, the reboot features three scientists. Abby Yates (Melissa McCarthy) and Erin Gilbert (Kristen Wiig) are particle physicists interested in the paranormal. Jillian Holtzmann (Kate McKinnon) is an engineering physicist. As the movie begins, Erin is working toward tenure at Columbia, which is ultimately refused, effectively resulting in her being fired (an homage to the 1984 film). Abbey and Jillian are working in the basement of the Higgins Institute of Science in NYC. While the storyline is quite different from the first movie, the reboot still uses science to explain and defeat paranormal phenomena. Just like in the first movie, there are harrowing moments, but as their knowledge grows and their experimental devices become more effective, they are capable of defeating not only ghosts, but erstwhile gods. While the original 1984 movie was a box office hit and one of the most successful comedies of that year, the 2016 reboot didn’t fare as well. They are both highly entertaining movies in my opinion--they simply employ comedy of different flavors. While the 1984 movie made a lot of childish jokes at women’s expense and employed a lot of goofy slapstick comedy and hyperbolic humor, the 2016 reboot acknowledged that, replied to it, and had its own flavor of quirky characterization that feels fresh and timely by comparison, especially to a more progressive or educated audience. Regardless of those elements, the concept was the same—use science to bring the inscrutable to light, defeat the paranormal bad guy, and make it funny.

2 Comments

The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty is truly a classic of the genre. Published in 1971, Blatty was inspired to write the book after hearing about a case of possession and exorcism that occurred in 1949 involving a teenaged boy in Maryland. Our instructor paired this book with the 2005 movie The Exorcism of Emily Rose, a modern tale of a college-aged American woman, which is based on the true story of Anneliese Michel in early 1970s Germany. (There have also been two other films made about Michel’s ordeal.)

Interesting parallels and differences can be drawn between these two narratives. Both involve young women, though Blatty’s possessed character, Regan MacNeil, was much younger, about eleven years old. In Rose, the possessed woman has just begun college, so we can assume she was eighteen or nineteen. Both seem to be unlikely candidates for faking possession—Regan simply based on age and Emily because she is a devout Christian. In Exorcist, psychological illness was ruled out. In Rose, Emily's mental condition was a mystery throughout. These two stories take different approaches. Exorcist is told in a linear fashion from the points of view primarily of her mother and the Catholic priest, Father Damien Karras, who becomes intimately involved with the case. Rose is more of a courtroom drama which goes back and forth in time to depict events from the point of view of whomever is speaking. For example, if a witness for the prosecution is relating their version of what happened, Emily is shown having epileptic fits and psychotic breaks, but when the Catholic priest Father Richard Moore delivers his explanations, Emily is portrayed as being truly demonically possessed. This introduces another element of uncertainty in the courtroom as well as in the viewer of the film. For me, the most fascinating parallel between the two stories lies in the willingness of both priests to sacrifice their lives—in the case of Father Karras, potentially even his afterlife—in their service. In The Exorcist, we are denied the opportunity to see Karras’s internal reaction to having the demon leave the child and enter his own body subsequent to him taunting the demon. This, I believe, is a flaw in this otherwise compelling narrative. Once the demon enters his body, we know that Karras leaps from the window to kill himself and block the demon from invading another human body. What the book fails to explain is that the Catholic religion teaches that suicide is a sin, and that Karras would be dooming himself to eternal damnation in that moment--quite a sacrifice to make. Throughout the novel Karras was tortured by his loss of faith, and therefore found it difficult to believe that Regan was actually possessed—so in the moment the demon possessed him he, at the very least, had to finally be certain of the existence of demons, which makes his sacrifice all the more poignant. The priest in Rose is equally willing to sacrifice, at least his life on this Earthly plane. Father Moore shows no signs of questioning his faith, or of doubting Rose’s possession. But the man is willing to risk spending the rest of his life in prison so that he may publicly tell Emily Rose’s story in order that her sacrifice would not be in vain. This is why he refuses plea bargains and insists on testifying in the courtroom, including reading aloud a letter Emily left for him. In this letter, Emily explains that she had a vision of speaking with the Virgin Marry who told her that she could be freed from her torment and ascend to heaven, or she could continue on, suffer greatly, but also serve as a reminder to humanity of the existence of the supernatural realm. Emily chose to see her ordeal through to the end. In both stories someone that is possessed dies, making a sacrifice for the greater good. In The Exorcist we assume that Father Karras’s death will protect others at the risk of damning his own soul. In Rose, Emily’s sacrifice is made to convince others of the existence of God in order to save their souls. In Exorcist, Blatty develops quite a few characters: the mother, Father Karras, even the male housekeeper. However, Blatty gives us very little characterization of Regan, the possessed. In a similar fashion most of the characterization in Rose is very shallow. The defense attorney probably gets the most screen time and yet even she is little more than a stock character. Both stories seek to shock us. Blatty has his little girl uttering obscenities and becoming freakishly strong and violent. Rose is more interested in chilling our blood with jump scares, animalistic screaming, horrific contortions of the young woman’s body, and animal attacks. Rose has a little bit more of the elements of more cheesy slasher horror. Both modes of storytelling are effective at what they set out to do. For me, though, I found the novel to be more compelling. I was particularly drawn to Father Karras's internal struggle. There is a reason that this novel's a classic that even young people today have heard of. Note: I haven’t seen the iconic movie version of The Exorcist (the screenplay was also written by Blatty) but the book is superbly written and the audio book (published in 2011)—whoa, Nellie!—the reading of the text is performed by the author and the man was (Blatty passed in 2017 at age 89) extremely gifted. If I hadn’t caught the first few seconds of the intro to the book, I would have assumed that the narrator was a consummate voice actor. It is a stunning performance including distinct vocal modalities for each character and a huge range of emotions.  I have seen first-hand that Black folks are exhausted by explaining race issues to white people. And yet they are required to do so again and again, usually because they are the only “expert” on the topic in the room simply by being there. Our culture is changing, waking up, and though it would be profane for me as a white woman to explain to a Black individual what their own experience means, I can, at the very least, educate other white folks on our collective blind spots concerning race—to the best of my ability. I hate seeing well-meaning but poorly informed white writers making the same old tired mistakes over and over again. So my goal here is to educate. I write inclusively in my fiction for that reason—but also so that Black individuals can see themselves in fiction as more than just a token representative. As you will soon see, there is more than one way in which King utilized race badly in The Shining and white writers can learn a lot from his mistakes. When the character of Dick Halloran popped up in the novel, I was surprised. I hadn’t read any King, but I’ve certainly heard people discuss his work for years. And I had gotten the impression that King wasn’t the sort of white male writer to include Black characters except in the capacity of either: a.) the Token Black Person or b.) the Black Person is the First to Die (or exists to die). I had forgotten that (at least) one more category exists: c.) The Magical Black Person. I’m referring to the novel, of course—in Kubrick’s movie adaptation poor Dick Halloran is ALSO forced into the role of both a and b. What is the Magical Black Person trope? Here’s how Wikipedia defines it (click on the link to read the entire entry if you want to learn more): The Magical Negro is a supporting stock character in fiction who, by use of special insight or powers, often of a supernatural or quasi-mystical nature, helps the white protagonist get out of trouble. African-American filmmaker Spike Lee popularized the term, deriding the archetype of the "super-duper magical negro" in 2001 while discussing films with students at Washington State University and at Yale University. Wikipedia goes on to list occurrences of this trope in film, television, and literature. The Shining shows up on both the film and literature list. But it doesn’t stop there. Writer and poet Scott Woods gives a lecture entitled “Stephen King’s Magical Negroes.” Woods takes this lecture seriously and keeps up with everything King writes (and has ever written) as well as every adaptation to television and film so he can update his lecture accordingly. His Medium essay on the topic is an interesting read. He notes, If you only ever watched The Green Mile, you’d have a decent-enough grasp on the problem here, considering John Coffey is not only King’s most famous Magical Negro, but perhaps the greatest Magical Negro of all time, right down to the religious hat-tip of his initials. You see, Dick Halloran isn’t King’s only magical Black man. He was just the first. King may have thought he’d written himself into a corner in The Shining. It is commonly accepted that in literature a protagonist must have the means and ability to save themself—and then do so. That’s usually the point of the story. But by making the protagonist a five-year-old boy—even a magical one--King may have worried that it would be impossible to believe that this particular protagonist could get himself out of serious trouble on his own. The kid needed an assistant strong enough to pick up his battered mother and carry her out of the Overlook Hotel before it blew. I posit that while reading it’s easy to forget that Danny Torrance is only five. His intelligence, actions, speech patterns—all are those of a much older person. I am the mother of two incredibly intelligent young men. They are the sons of an author who favors a large vocabulary. And they, at age 10, couldn’t rival Danny Torrance at age five. It’s as if the shine has increased his experience of the world 100-fold. In fact when Danny pleads with the hotel near the climax of the story, (I’m just five!) he cried to some half-felt presence in the room. (Doesn’t it make any difference that I’m just five?) I sort of twitched. That reminder shocked me. Danny Torrance is so young he has never met another person like himself until he meets Halloran. Halloran takes the time to explain the shine to Danny and the words that he speaks rebound through Danny’s mind throughout the rest of the novel. Of course Halloran was wrong about one thing—he doesn’t take into account that the sheer supernatural power Danny wields could fuel the hotel. Or that it might want all that power for itself. So in the end Danny is forced to psychically scream in order to get Halloran to come back to this remote spot in Colorado all the way from Florida. Which he does. And though he immediately gets beat up by the Jack/Hotel construct, he does manage to get Wendy and Danny out of the hotel—and away to safety via a snowmobile in the deadly sub-zero winter temperatures. One might say—hey, Jen, this was 1977. Give King some props. He made a Black man a pivotal character in this novel. He didn’t have to do that. Keep reading. As we watch Halloran struggle to get to Danny, Halloran is subjected to what felt like (to me) constant racial slurs, including the N-word. This was another of King’s painful mistakes. I’m sure he thought he was writing realism. In his essay, Scott Woods calls this the “Tarantino Defense.” But for African American readers, the result is the same. Whether a writer is racist and writing his own beliefs or simply writing characters who would realistically say those horrible things, the psychological damage of reading them is the same. As a white woman, I felt sick reading them. Why are they needed in this novel, in any novel? What purpose does it serve? King could have toned it down to Halloran having feelings of being unwanted or hearing unkind words and every living American would know what he meant without resorting to such backwards and sickening language. Did he think no African American would ever pick up this novel? Did he think that if they did they were inured to such violent language? No one becomes immune to hearing or reading damaging words like that. Words have power. If we don't know that, we shouldn't be writing. While The Shining is brilliant in so many ways—while it was a trailblazer in the Horror genre, a classic—things that shine are subject to tarnish. The use of the magical Black person and the liberal use of realistically stark and biting racial epithets mars this novel. I realize I may be pissing off serious King fans. But remember—no single thing is perfect. Let us go forth and always try to do better. Post Script King may have long been a vocal liberal, but according to Woods, it’s only in the last few years that King has become woke enough to tweet something like this from 2016, right after the acquittal of the police who killed Freddie Gray: Woods also noted significant changes among the pages of King’s 2017 novel Sleeping Beauties which King dedicated to Sandra Bland, the Texas woman who was wrongfully arrested for driving while Black and then mysteriously died in her jail cell three days later.

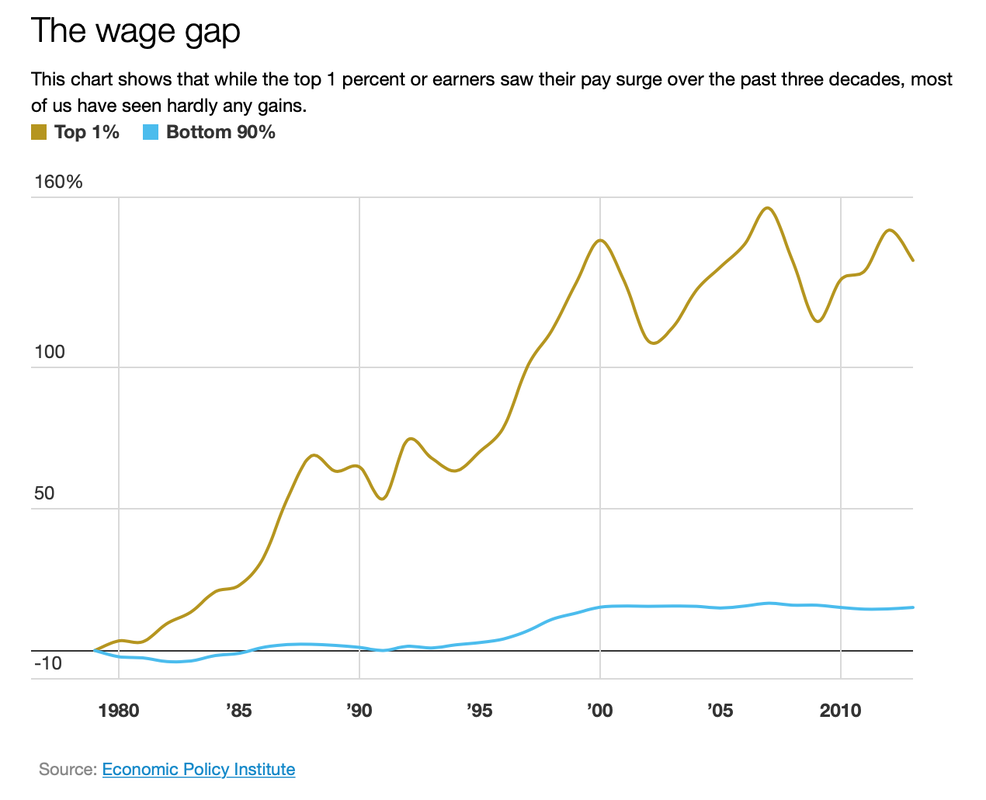

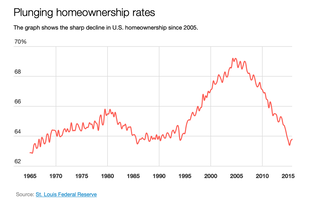

Stephen King is 74 years old. If he can change at that age, we all can.  Stir of Echoes demonstrates a post 9/11 trend I’ve noticed in dystopian literature—that of allowing the protagonist to have agency and to effect change in their world or surroundings. For example, in The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood, Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell the protagonists have no agency and the central story problem is not resolved. But after September 11, 2001 popular dystopian novels like The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, Ready Player One by Ernest Cline, and Divergent by Veronica Roth allow the protagonists to reshape their world for the better. Now I realize we have been studying horror and not dystopian literature, but since they both fall into the realm of speculative fiction, I think this is an interesting quality to note, though in the case of these horror/ghost stories I don’t see it as a trend with a specific pivotal date. In many of the stories we’ve read and watched this semester the end of the book reflects the conclusion of the story, but not necessarily a resolution of the original problem i.e. the haunting. In The Haunting of Hill House, Paranormal Activity, Nightmare House, The Others, and The Amityville Horror, the haunting continues throughout the story and beyond. By contrast, Stir of Echoes, Hell House, Ghost Story, and Grave’s End each give the protagonists the means to end the haunting. Allowing the protagonists to find a solution doesn’t just kill the chance for either a sequel or a franchise to be developed around the same premise, it also removes the horror element. Horror could be defined as contact with the sublime—a manifestation of the unknowable, the awe-inspiring, the terrifying, something we mere mortals cannot measure or understand. But if the protagonist comes to at least a minimal understanding of the central problem of the story—enough to eliminate the problem or to set things right again—then they have peeked into the sublime and learned something. And that removes the horror. When Kevin Bacon, as Tom Wiztsky, finds himself confronted with bizarre and frightening messages from beyond the grave, he doesn’t run away—instead he seeks to understand. He sees the messages as clues, as some riddle he can solve, despite the fact that the process seems to be driving him mad. And even when his wife loses faith in him, he declares that following this trail of clues is the most significant, most important thing he’s ever done in his life. We find out how deep his passions run when he digs up the entire back yard, then proceeds to rent tools to break through the concrete flooring in the tiny basement space under his kitchen. Ultimately, very much like one would in a mystery story, Wiztsky solves the problem that caused the spirit of a young woman to haunt his house. He brings her killers to justice which frees her soul from its dark despair and allows her to move on. The haunting has ended. Similarly, the protagonists of Hell House, Ghost Story, and Grave’s End solve their respective mysteries and the haunting element is eliminated. That’s not to say Stir of Echoes didn’t have frightening or horrific moments—there were a few moments of body horror here and there that are still making me cringe. And of course the way that Tom Wiztsky seemed to be losing control of his life was also frightening. I don’t necessarily see this as a similar trend to that which I have noted in dystopian fiction, but more of a stylistic choice. I think most readers find an ending with a full resolution to be more satisfying, and uplifting--and less frightening than one in which there is no hope of solving the story problem. But if an author’s goal is to curdle the blood and make the novel hard to shake for a reader, I would suggest not allowing the central story problem to resolve. Haunted by the American Dream  The American Dream has always been perceived by Americans as the trend toward upward social mobility for the entrepreneur, the determined, and the hard working. It’s the ability to go from rags to riches—or at least to a prosperous middle class. It is home ownership. It is stable employment--the ability to retire debt-free, and enjoy one’s golden years without fear. Of course, this fantasy has never applied equally to race, class, or gender. Many view the American Dream as the possibility of one’s children doing better, financially, than their parents. However, according to Brookings, “While 90% of the children born in 1940 ended up in higher ranks of the income distribution than their parents, only 40% of those born in 1980 have done so.” For all but the highest paid workers, wages have been in decline for the last 30 years. In 1950 CEOs were paid an average of twenty times the pay of typical workers. That multiple rose to 42-to-1 in 1980, and to 120-to-1 in 2000. The rich grew richer while the poor became poorer. Homeownership rates have recently hit a fifty-year low, below sixty-four percent, in 2015. Many ambitious books have been written about this complex decline in hope for upward social mobility among the poor, so I won’t cover that in depth here. There are, of course, many factors contributing to this trend (some I've already touched on): inflation, wealth inequality, racism, among others.

In 1977 when Jay Anson wrote his pseudo-true haunted house story The Amityville Horror, the American Dream was still achievable for a white middle-class family. This story, written more like true crime than a typical novel, follows the Lutz family as they choose a new home in Amityville, Long Island. With an $80,000 price tag—far below the going rate for this posh neighborhood due to the house having been the site of a mass murder—it is still somewhat above George and Kathy Lutz’s means, but they can’t pass up the opportunity. They decide to overlook the home’s past. After all, they aren’t superstitious people. Like many who attempt to live beyond their means, the Lutz family is just a single disaster away from losing everything. They are a single-income household, attempting to live the 1950s idyllic lifestyle with Kathy at home, filling her days with house-making chores and caring for the children, while George goes off to manage his small company. Throughout the novel, George Lutz frets over how he’s going to pay the bills and he’s shuffling money around from his small business accounts to his private accounts to cover checks he’s already written--even when he knows his business is about to be audited. Everything goes askew when the house turns out to be haunted. The story is full of details of their swift decline in fortune. Doors are ripped off hinges, windows are broken. George watches his wife levitate and listens to his pre-school-aged step-daughter describe conversations with a demon pig as if it were her best friend. Sludgy green goo emanates from a door lock and oozes down walls and staircases. Flies congregate midwinter. A strange hidden room—painted red and reeking of blood—is found in the basement. Kathy Lutz feels the hands of an invisible stranger. Strange smells permeate the air. Even the priest who tried to help them is plagued by stigmata and bedridden by stomach flu three times in three weeks. Ultimately, the Lutzs are driven from the home, leaving all of their possessions behind, and move far away, to California. The real Lutzs, who dreamed up this over-the-top confabulation, were also reportedly in some financial troubles, though that had to have eased significantly after royalties from this book poured in. But I have to wonder, were the Lutzs haunted by ancient demons or by the specter of intractable debt destroying everything they ever thought they wanted? References and Further Reading: Brookings Institute "Is the American Dream Really Dead?" Economic SYNOPSES 2015 I Number 14 "Lagging Long-Term Wage Growth" Economic Policy Institute "CEO Compensation has Grown 940% Since 1978" Wikipedia "Wage Ratio" The Conversation "Is the American Dream Dead?" Investopedia "What Does the American Dream Mean To Different Generations?" When I think of haunted houses, I frequently think of this Eddie Murphy skit. He’s just so sensible. White people do stick around too long in these stories. As viewers we're all silently shouting at the screens--just get out! But as writers we know that if we have our characters “just get out” there will be no story at all. It’s fine for a comedy skit, but not the blockbuster novel we’re dreaming of writing. Q. Why would a person stay in a haunted house?  As I read Elaine Mercado’s Graves End: A True Ghost Story, I kept thinking about the similarities of her experience in that home to an abusive relationship. Sometimes it’s just not a simple matter to extricate ourselves from the situations we humans find ourselves in. Here are the ways that I felt Elaine Mercado’s experience mirrored an abusive relationship: Whether an abusive relationship takes the form of physical or emotional abuse, the victim of the abuse suffers from low self-esteem. They have been repeatedly made to feel worthless and like there’s no better option.

The abusive cycle. Instances of abusive behavior are often followed by sincere apologies and promises that it will never happen again. Then there is usually a honeymoon period of extreme solicitousness.

Societal pressure. There is less of this these days than in the past, but there can be a lot of pressure--especially from family--to stay together for the kids, or to stick it out through a bad patch, because it will get better.

Gaslighting. Abusers are often adept at making their victims feel as though all of their problems as a couple are the fault of the victim.

Maybe they’ll change. A lot of people in these situations live on the hope that their partner will change.

Dependency. Often people can’t just leave an abusive relationship because they have children with their abuser or they may be inextricably tied financially to them with shared accounts and properties.

We’ve all read stories with thin premises. As writers it’s important to consider real-world reasons for our character’s motivations so that they make sense to the reader and are believable. While this story is a memoir of a real individual’s experience, I think that we can learn a lot by examining the nature of her reasoning and thought processes and how they may parallel other situations that we may be more familiar with—and bring those ideas with us into the writer’s room.  Warning: there are spoilers in this post! This film, released in 2001, was written, directed, and scored by Alejandro Amenábar and stars Nicole Kidman. The movie was a box office success and critically acclaimed both due to Kidman’s performance and Amenábar’s clever script. I posit that this script is a perfect example of asking all the right “what if” questions in order to arrive at a unique story with a killer surprise ending. When we sit down to write a story we are asking ourselves many “what if” questions as we contemplate every aspect from characterization to plot. I can only presume that Amenábar set out to write a Gothic Horror script that subverted expectations and played with typical notions of time and space. In this essay, I’ll imagine how Amenábar worked through these questions. Perhaps he began with the genre convention of a spooky mansion but asked himself, “what could make this house more spooky?” Perhaps it is half empty and half filled with the previous owner’s belongings, covered with sheets. Maybe it is dark all of the time inside, to make it extra spooky. Then comes the question, “why would it be dark inside all of the time?” Amenabar decides that the story is set just after World War II. The family is so accustomed to living without electricity due to all of the outages during the war that they never bother to have electricity installed. That would make the house much darker inside—especially at night. The inhabitants would be forced to rely on candle and lamp light. That means small pools of flickering light and deep shadows—a perfect setting for one’s mind to play tricks. Perhaps he thought, “This is good, but it would be even better if it were also dark during the daytime. What reason could there be for darkness inside the house during the day?” Perhaps he had heard of the rare disease Xeroderma pigmentosum. One would have to assume that with only 1000 modern cases in the world, there would be people afflicted with the condition in the 1940s, but it would not be well understood. This genetic disease causes an intense and dangerous reaction to sunlight. Most afflicted children do not make it to adulthood because limiting sun exposure is so difficult. This not only fulfills his need to make the enormous mansion dark and spooky even during the day but it also adds an element of high stakes—the children must be protected from light and even the smallest misstep could have dire consequences. Things must be muddled. Let’s make the mother a strict disciplinarian who is clearly off-balance—make the audience wonder if she is on the verge of a nervous breakdown or another form of mental illness. And add three other characters in the form of servants, who sometimes appear to be generous and kind and other times seem to be acting very suspicious. Make the mother desperate for help, such that she takes them on without references. Also, throw in a husband, thought to have died in the war, who is shell-shocked from trench warfare.  Now, Amenábar may have thought, how can I subvert my audience’s expectations? A surprise twist at the end. Yes. Perfect. We always read and watch ghost stories from the human point of view. Is there a way we can turn this on its head? Ah, yes. Write the story from the ghost’s point of view. Can we make that even stranger somehow? The mother is unhinged... perhaps she doesn’t know she’s dead. Perfect. What other elements could be added to make things extra creepy? The little girl could see things that the adults can’t. Throw in a photo album full of death portraits, mysterious fog, unseen children crying and playing, doors that shut on their own, and pianos that play themselves. Anything else? Make the mother so neurotic she not only closes every door, she locks them. Perhaps one more genre convention to round things out. A seance led by a spiritualist. Yes, that plays into the twist at the end perfectly. I hope Alejandro Amenábar will forgive me for supposing I can imagine his thought processes, but I found this plot and characterization so fascinating, so refreshingly new, that I had to think about how he may have come up with it. Thinking this way—in particular: how do I subvert the reader/watcher’s expectations and surprise them—can really make for a fresh take on a common story. Readers want to read stories that feel comfortable and familiar while also surprising them. It behooves us as writers to imagine what elements of common genre conventions we wish to use on their face and which ones we want to contort into something new. In this case, the dark, lonely mansion and the mentally ill woman living in the house are genre conventions. But most of the rest of this story feels entirely new. I think that is the secret to this movie’s success. Kidman’s incredible performance didn’t hurt either. Postscript: Unfortunately, at the time of this writing, The Others is not available on any US streaming service. I believe this may have something to do with a television adaptation in development.

Delete both the cover and the publishing date from Douglas Clegg’s Nightmare House and some readers may have a difficult time guessing when it was actually published (my kindle edition was published in 2012). Set in the early twentieth century, this delicious gothic horror novel of Esteban “Ethan” Gravesend’s deeply personal encounter with his inherited haunted mansion utilizes many of the elements of novels from the past. As I read, I was reminded of the flavor of such classics as Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, by Charlotte Bronte and Emily Bronte (both published in the mid-nineteenth century), but I noted that several reviewers on the book’s Amazon page mentioned Henry James’s Turn of the Screw (known to be greatly inspired by Jane Eyre—but with ghosts) which was published just at the turn of the twentieth century and is also a gothic horror novel.

The prologue sets the stage by describing the narrator/protagonist’s entire life, from birth, including his relationships with his parents (and a brief summary of their lives), as well as his remembrances of the titular mansion from childhood when his grandfather was still alive. This convention of the past is no longer considered normal or acceptable in popular fiction. As modern writers we are expected to begin our novels in medias res (into the midst of things, without preamble). Chapter one continues on in this vein, discussing more of Ethan’s life, his marriage, and more remembrances of his grandfather and the estate Harrow he will one day inherit from him. In this novel, I found some of this tedious, but only briefly, because the details were not only interesting—they became pertinent later in the story. By part six of chapter one, the story actually begins. Another interesting device Clegg used from popular fiction’s more distant past is the use of a digression. Digressions are interruptions in the flow of the novel to temporarily switch to another topic. In this novel, these occurred whenever the elderly Ethan interrupts the narrative of the story to tell the reader something he deems important. Traditionally these were often used rhetorically, to further convince a reader of the veracity of a claim. I believe Clegg used these digressions consciously as a stylistic choice to create the feeling of a period gothic novel. Dark, disturbing family secrets also figure large in all of the novels mentioned, usually revealed toward the endings of these novels, often as part of the climax. Here, too, this story reveals some disquieting secrets. Clegg also utilizes what I assert is another convention of these novels from the past—the orphaned child, the unloved child, or the unhappy childhood. Just like Jane Eyre and Heathcliff (of Wuthering Heights) Ethan’s childhood is not what it should have been. His mother pretends to be an invalid and secretly sleeps with her “doctor.” And his father seems to abhor him. The reasons for these attitudes is revealed in the exciting climax of the story. Clegg’s use of language also harkens back to an earlier time. It’s just that little bit more flowery, with more complex sentence structure, than we tend to use today. The text was still quite clear and easy to read, however. He didn’t take this affectation too far. I found his approach effective. Here’s an example: My young life was uneventful save for my naming. My mother—since the accident that precipitated my birth—claimed a weak heart. Her many medications were famous among us: she could not leave her bed without a spoon of some remedy; she could not kiss my father good morning without some wee dram of medical potion to get her heart to its normal capacity; and she often spent months at spas in Saratoga and across the sea—leaving me with a nanny and my father, neither of whom I particularly liked.

Douglas Clegg intentionally used writing conventions of the past to give his novel the distinct flavor of a period gothic novel. He utilized slightly more antiquated language, digressions in his narrator’s voice, an unhappy childhood for his protagonist, disturbing family secrets, and a very detailed summary of the protagonist’s life up until the moment the story begins. I found Clegg’s use of these elements in Nightmare House to be not only effective but also charming. As a young adult I was quite enamored with the Brontes’s works and adaptations of their works as well as other period dramas so perhaps it’s no surprise that I found this novel appealing as well.

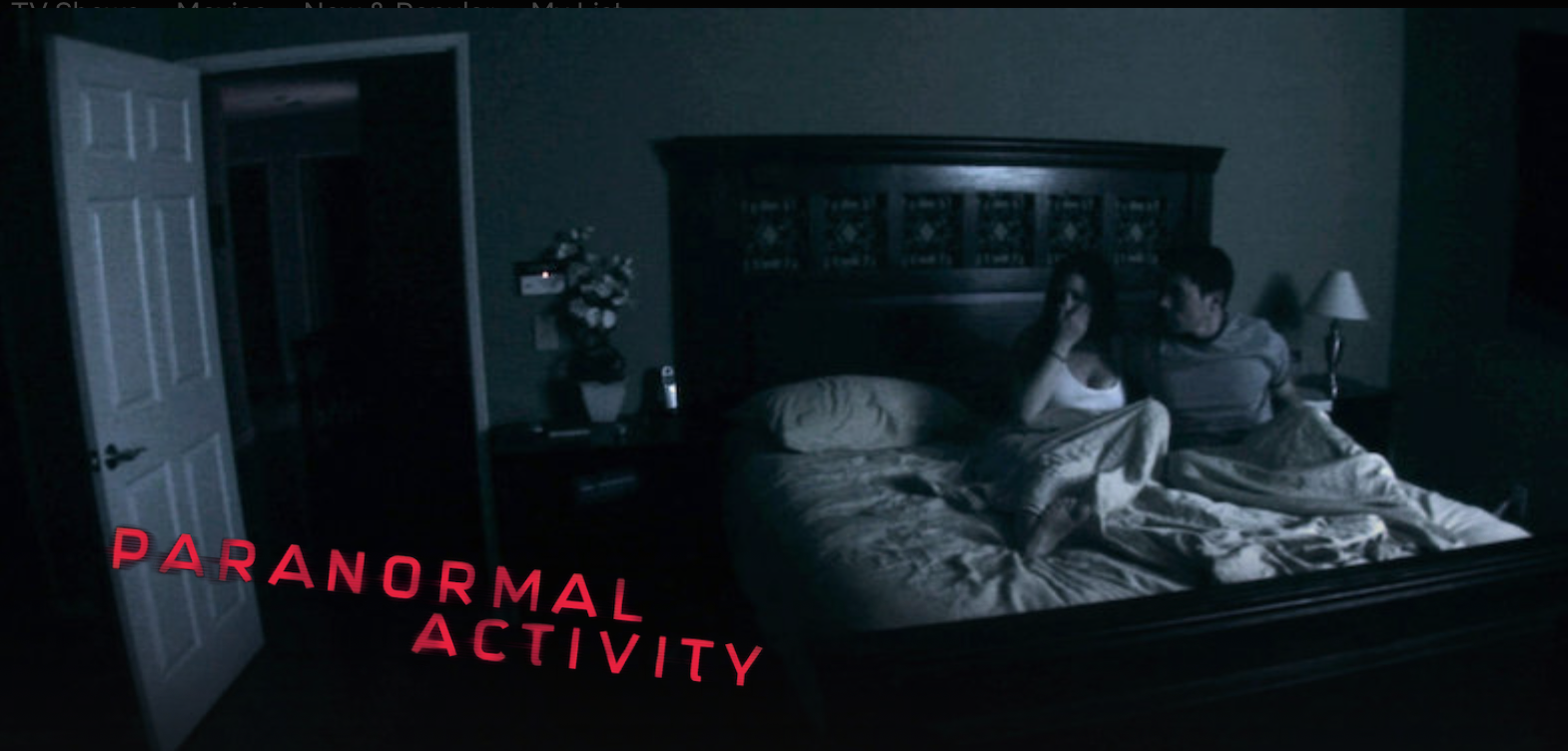

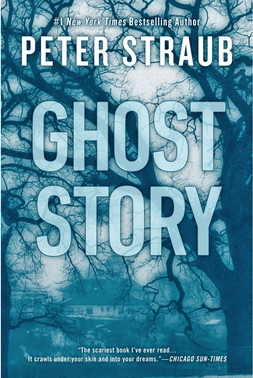

A footnote: I could easily have explored further how Clegg utilized gothic novel conventions and/or elements of American Romanticism in this piece, but I felt that the elements I mentioned would be more useful to modern writers of popular fiction. (This could quite easily turn into a full-blown academic treatise.) If you wish to explore these elements further, these sites present quick and easily digestible summaries: Invaluable on Gothic Literature ThoughtCo on American Romanticism *Some links in this post are affiliate links which reward me with a tiny commission at no cost to you.  Ghost Story by Peter Straub employs an unusual and fragmented story structure as well as an atypical use of point of view. This is not just a horror story. It’s also a mystery. Straub used many techniques writers are generally discouraged from using. It’s rather ambitious and I wouldn’t recommend this route for someone new to writing, but in Straub’s hands it worked amazingly well. The prologue, often advised against in modern fiction, is a brief and disturbing vignette. Once I started reading the book itself, this prologue made little sense (as they often do) but in this case thoughts of that prologue kept surfacing as I read because it had been so disturbing. At some point after Don Wanderly was introduced I realized he was the narrator of the prologue and I tried to figure out how he could have been driven to that point. The why of it isn’t revealed until the epilogue—a brilliant use of those two sections of the novel. Part one of the novel tells the story of a group of four (originally five) elderly men, all in third-person omniscient point of view. These first chapters spend a lot of time establishing character and move slowly, weaving in and out of their memories through flashbacks and stories (Flashbacks aren’t universally discouraged, but I have definitely seen readers complain about them). We learn that this group’s bond is strong and forged in young adulthood. Aside from Ricky, who is the point of view followed most, and Sears James—only because he’s cantankerous and I like those sorts of characters—the other three men felt somewhat less distinct and I had some difficulty remembering who was who unless or until Straub gave some hint. It’s always difficult with a large cast to create fully distinct and memorable characters, which is why new writers are advised to stick to smaller casts. It turns out the large cast is necessary—to die horribly and to seed clues about the antagonist. Surprisingly, part two of the novel follows a new character, one that had been mentioned but we had not yet met: Don Wanderly, the nephew of the first of the elderly men to mysteriously die and a writer of a popular horror novel. These chapters are in first-person point of view--the conceit being that we are reading his journal. This occurs twenty-seven percent of the way through the novel. Most novelists would be discouraged from making such a huge shift mid-novel. There were points when I was so immersed in Don Wanderly’s story that I completely forgot part one and all the elderly gentlemen. Truth be told, this is where the novel picked up for me and started to get really interesting. In part three, sixty percent into the book, Straub brings these men together and we begin to get an inkling for how all of their stories are connected. We’re also back to third person omniscient point of view for the remainder of the novel. Peter Barnes, a high school senior who we met in part one briefly, grows in importance as a character. By the end he, Don, and Ricky could all be described as protagonists. The book is really picking up steam now with hair raising scenes and several deaths, more stories and flashbacks. When Don Wanderly takes a turn at being the focus of point of view his chapters are now being told from third person omniscient like the others. By the end of the novel, all of the disparate pieces of the story are brought together and the mystery is solved. The three men left standing face off with the antagonist and win. Mostly. It happens rather quickly and I do think Straub could have drawn this scene out a bit more. I also had to reread it a couple of times to be sure I understood the sequence of events. The most delicious part of this book comes in the epilogue—another novel element that isn’t often used. We are back with Don where the prologue left off. We’ve come full circle now and we know why Don is in the state he’s in and we’re rooting for him. He defeats the antagonist and we are treated to complete satisfaction like so seldom happens in horror fiction. In this novel Peter Straub utilized some unusual techniques. Minor characters became major characters more than halfway through the book. Point of view changes type for one third of the book. There are scads of characters, a prologue, an epilogue, and lots of stories and flashbacks. It could have been a recipe for what not to do, but somehow Straub makes it all work and I was left feeling like he was ingenious. In 2009, when Paranormal Activity was in theaters, I was stuck at home with a colicky baby. I remember next to nothing of popular culture of that time, so it's probably no surprise that I hadn't heard of this film before it was assigned to me in my current Readings In Genre class. This is a "found footage" style movie like Blair Witch, but this amateur filmmaker has a steady-cam and a tripod, which makes for less-nauseated viewing. The premise--that a young woman has been bedeviled by nighttime paranormal activity since she was eight-years-old--was plausible and though the acting felt stiff and forced in the beginning, this couple quickly hit their stride in this unscripted production that was filmed for only $15,000 and grossed more than any other film in history. This movie is proof that one doesn’t need a huge budget, elaborate set, or dozens of famous actors to make an effective and successful film. It’s all about the story one tells—and the way it’s told.  Shot entirely inside a two-story home, day and night, over the course of one week, the setting seemed utterly realistic and the couple improvised their dialogue, even flubbing their speech naturally, to the point that I quickly suspended all disbelief and became engrossed in their troubles. I really liked how the haunting seemed to progress in this tale. Micah gets more and more agitated as he attempts to understand and solve the problem. In turn, Katie's fears are amplified, and the entity--which seems to be feeding on her fear--grows stronger. One of the things I appreciated about this flick was the choice to keep the violence off-camera, more like classic horror films. You can do a lot with the power of suggestion—and save a lot of money on CGI. I personally don't believe that seeing violence makes a movie more scary. The unknown is what is scary. Whatever happened to Katie and Micah in that dark back bedroom is terrifying enough when we simply hear the sounds and see their shock-stricken expressions. I'll admit to having to remind myself that it was just a movie more than once as I watched. It really has the feeling of a docudrama. I especially liked the time lapse footage when they were sleeping. And in this instance at least, the found-footage conceit really works. By the end, the couple has generated so much chemistry that their body language, expressions, and actions felt entirely true. The close quarters and grueling work of 24/7 filming for a week probably contributed to that feeling that they were a real couple in the middle of something terrible.

What this film really demonstrates is that a haunted house need not be a lavish mansion or even be set in an exotic or remote locale. A plausible premise, believable characters, and a series of spooky occurrences will set people's spines twanging. Short scenes like them woodenly eating take-out with blank stares added to the realism. The tension increased as the characters make bad judgement calls, disagree with each other, and get strange advise from a psychic. Suddenly a door moving on its own or a swinging light fixture becomes terrifying. We can do the same thing with our fiction. A haunted house story doesn’t have to be set in a dark and stormy night in a ramshackle house on the edge of a cliff. With a good plot, plausible premise, and realistic dialogue, a spooky atmosphere can take over any locale—and give us the shivers we desire. |

Jennifer Foehner WellsI'm an author of the space-opera variety. Archives

April 2022

Categories |